8/07/2012

8/02/2012

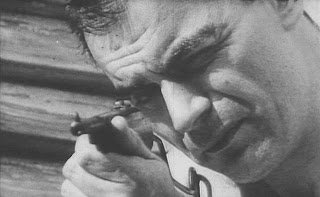

Poslijepodne (puška) - Lordan Zafranović

Poslijepodne: vrućina, omara - sunce udara ravno u tijelo, mozak, u sljepoočnice.

Siesta u nekom splitskom dvorištu, ljudi preživljavaju težak ljetni dan.

Zvizdan će proći, sve će se nastaviti dalje, ali... jedan će život biti ugašen.

Žrtva ovog običnog dana (a sasvim neobičnog!) nevina je ptica.

Njezina razjapljena, žedna usta optužuju: Zašto? Čemu?

Nizašto. Nizbogčeg. Tek iz puke dosade.

"Poslijepodne / Puška" (1967) igranofilmska je vježba Lordana Zafranovića. U njoj propituje korijene podsvjesnog zla. No to je zlo zapravo toliko uobičajeno, da je postalo svjesnim. U vrućem poslijepodnevu oronuloga gradskog dvorišta Mladić (Tom Gotovac) zabavlja se gađajući zračnim oružjem predmete oko sebe.

Dramaturški nerv unosi Dječak, koji mu donosi nemoćna vrapca kao metu. Na kraju, ubijanjem i mrcvarenjem ptice, iskazuje se sva iracionalnost zla zaslijepljena vrućinom u dokolici besmisla.

Između svih Zafranovićevih minijatura tj. kratkih filmova iz klubaške faze, ova je ponajviše "zafranovićevska". Lica starica, grudi žena... muha na mrtvome vrapcu - poetika sasvim njegova. Jer, tko će u istoj sekvenci moći spojiti ono najuzvišenije i ono najprizemnije.

Sunce u zenitu - raspadanje strvine, baš to je "Poslijepodne / Puška".

Marijan Krivak - Zapis br. 68 (HFS)

P.S.

Poznati su vam kadrovi s Tomom Gotovcem i zračnim oružjem? Koristio ih je, nekoliko godina kasnije, Lazar Stojanović u filmu "Plastični Isus".

Za EX FILMOFILE Anamnesis

7/17/2012

M (Fritza Langa) by Claude Chabrol

| Fritz Lang: M - Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder |

Njemački velegrad u stanju je opće panike: psihopat kojemu je, čini se, nemoguće ući u trag, siluje i ubija djevojčice. Policija, kojoj on piše izazivačka pisma, na čelu s inspektorom Lohmannom uzalud se prihvaća svih metoda istrage - od najsuvremenijih grafoloških i psihoanalitičkih do maksimalnog povećanja broja racija u sumnjivim četvrtima. Ovo posljednje uznemiruje podzemlje na čelu s inteligentnim, okorjelim kriminalcem Schrankerom, koji jedini izlaz vidi u vlastitoj inicijativi, angažiranju organizacije prosjaka. Krug se počinje zatvarati oko mirnoga građanina Beckerta, a indicija je zviždanje motiva iz Griegova Peera Gynta. (video)

| Claude Chabrol: M le maudit |

Francuska televizija osmislila je serijal kroz koji će poznati redatelji snimiti kratki remake - do 13 minuta - svoga omiljenoga filma. Claude Chabrol, prvi dobrovoljac, izabrao je remek-djelo Fritza Langa "M" iz 1931. godine. Maurice Rich, u eksperimentu "M le maudit" (1982), nosi ulogu koja je Petera Lorrea učinila slavnim.

Za EX FILMOFILE Anamnesis

6/26/2012

Zabranjene igre - Rene Clement

Jedan od filmova s intimne liste Najveći svih vremena, i ulomci jednog od najboljih eseja na temu istog...

Cinema is a photographic trace of life. For that reason, it's also a perpetual witness to mortality. Georges Poujouly, the child actor who stars, with Brigitte Fossey, in Rene Clement's 1952 masterpiece "Forbidden Games" (Jeux interdits), died in 2000, at the age of sixty. But as Michael, the rude peasant boy at the beck and call of the imperious baby Paulette, he remains the image of enslaved, amorous youth forever. That's both the consolation of cinema and the source of its hidden melancholy. For, naturally, most films repress the knowledge that they are destined to become graveyards teeming with ghosts. "Forbidden Games" is among the few that dare to break this ultimate taboo. Here is a movie obsessed - even besotted - with death.

Set during the German blitzkrieg of Paris, in June 1940, the film opens with a mass of refugees fleeing the despoiled capital for the countryside. Suddenly, Luftwaffe planes streak into view, raining down terror and scattering the people on the ground like marbles. Clement choreographs the mayhem with a stark authenticity that validates his youthful training as a documentarian. At the same time, the scene is - ever so slightly - a pastiche or compendium of erlier war rhetoric in cinema.

One shock cut (from a bomb dropping on the camera to a woman screaming in close-up) is straight out of Eisenstein, while the present-tense casualness of the violence evokes Roberto Rossellini's "Open City" (1945) and "Paisan" (1946) - not to mention Clement's own previous foray into neorealism, the Resistance docudrama "Battle of the Rails" (1945).

The subtle quotation marks around the action hint that the movie is perhaps less "real" and more ironic than it's cracked up to be. For already a certain fantasy dimension infiltrates the harrowing imagery of war. When bullets from a machine gun tear through the backs of Paulette's mother and father, the murder feels sickeningly contingent. Yet pasted on the bridge where they happen to be (and almost subliminally planted in the frame) is an advertising bill for spiritualists - "master of mystery". Both the bridge and the river flowing under it are thereby instantly changed into supernatural objects: emblems of transience, gateways dividing the quick from the dead. Similarly, a horse pulling a driverless carriage at a furious gallop is both an ordinary frightened beast and an uncanny figure of doom. It's this vehicle that Paulette capriciously follows, abandoning the contemporary slaughter, straying into an enchanted region where death will attain the perverse beauty of an idyll.

Her crossing over is signaled by the introduction of Narciso Yepes's famous guitar solo. (video) Naive and plangent, the music almost literally haunts the film, summoning an ache of nostalgia for some pristine era beyond memory.

Christian forms are simply the pretext. These ghoulish games seem finally to invoke something more archaic and terrible - a mystical awareness, which might be called pagan, of nature's unending cruelty. But Clement respects the enigma, and each plausible interpretation of the children's conduct slips helplessly through one's fingers. It may be supposed that Paulette is a model trauma victim, incapable of absorbing her parents' death and obliged to grieve for them at second hand. That's the easy, clinical rationale, and war's thunder does continue to echo distantly on the soundtrack, as if in corroboration. Still, it isn't sufficient to account for the element of precocious eroticism that tinges her relationship with Michel, insinuated by the faint double entendre of the movie's title.

Paulette is a diminutive version of the femme fatale in film noir, batting her huge, liquid eyes and spurring the mesmerized hero on to ever greater acts of bloodlust - with one crucial difference: Paulette is no bad seed out of a horror movie, but a completely ordinary toddler. Though Clement doesn't stipulate her motives, we may deduce that they involve plain childish calculations of self-interest. Having lost one source of security and well-being, she casts around her environment and pragmatically reattaches her desires elsewhere. The supreme tour de force of Fossey's naturalistic acting occurs in the aftermath of the bridge disaster. Touching her mother's cheek and then her own, Paulette puzzles over the rudimentary concepts of warm and cold, alive and dead. The impious rites with corpses, the whole film, might be explained by the necessity of returning, again and again, to this compelling riddle that reality has tossed up.

For kiddie necrophilia, Paulette has no rival - unless it be young Tootie Smith, who ascribes four fatal diseases to her rag doll and babbles endlessly about homicide in Vincente Minnelli's so-called family musical "Meet Me in St. Louis" (1944). Much later, another little girl would use scrambled Christian ritual to commune with her deceased mother, in Jacques Doillon's "Ponette" (1996). Yet "Forbidden Games" is perhaps the one movie wholly dedicated to the radical Freudian proposal that living matter seeks the comfort of oblivion. Seductive and troubling, it remains the chief embodiment of the death drive in cinema.

Peter Matthews (The Criterion Collection / Sight & Sound)

Za EX FILMOFILE Anamnesis

Cinema is a photographic trace of life. For that reason, it's also a perpetual witness to mortality. Georges Poujouly, the child actor who stars, with Brigitte Fossey, in Rene Clement's 1952 masterpiece "Forbidden Games" (Jeux interdits), died in 2000, at the age of sixty. But as Michael, the rude peasant boy at the beck and call of the imperious baby Paulette, he remains the image of enslaved, amorous youth forever. That's both the consolation of cinema and the source of its hidden melancholy. For, naturally, most films repress the knowledge that they are destined to become graveyards teeming with ghosts. "Forbidden Games" is among the few that dare to break this ultimate taboo. Here is a movie obsessed - even besotted - with death.

Set during the German blitzkrieg of Paris, in June 1940, the film opens with a mass of refugees fleeing the despoiled capital for the countryside. Suddenly, Luftwaffe planes streak into view, raining down terror and scattering the people on the ground like marbles. Clement choreographs the mayhem with a stark authenticity that validates his youthful training as a documentarian. At the same time, the scene is - ever so slightly - a pastiche or compendium of erlier war rhetoric in cinema.

One shock cut (from a bomb dropping on the camera to a woman screaming in close-up) is straight out of Eisenstein, while the present-tense casualness of the violence evokes Roberto Rossellini's "Open City" (1945) and "Paisan" (1946) - not to mention Clement's own previous foray into neorealism, the Resistance docudrama "Battle of the Rails" (1945).

The subtle quotation marks around the action hint that the movie is perhaps less "real" and more ironic than it's cracked up to be. For already a certain fantasy dimension infiltrates the harrowing imagery of war. When bullets from a machine gun tear through the backs of Paulette's mother and father, the murder feels sickeningly contingent. Yet pasted on the bridge where they happen to be (and almost subliminally planted in the frame) is an advertising bill for spiritualists - "master of mystery". Both the bridge and the river flowing under it are thereby instantly changed into supernatural objects: emblems of transience, gateways dividing the quick from the dead. Similarly, a horse pulling a driverless carriage at a furious gallop is both an ordinary frightened beast and an uncanny figure of doom. It's this vehicle that Paulette capriciously follows, abandoning the contemporary slaughter, straying into an enchanted region where death will attain the perverse beauty of an idyll.

Her crossing over is signaled by the introduction of Narciso Yepes's famous guitar solo. (video) Naive and plangent, the music almost literally haunts the film, summoning an ache of nostalgia for some pristine era beyond memory.

Christian forms are simply the pretext. These ghoulish games seem finally to invoke something more archaic and terrible - a mystical awareness, which might be called pagan, of nature's unending cruelty. But Clement respects the enigma, and each plausible interpretation of the children's conduct slips helplessly through one's fingers. It may be supposed that Paulette is a model trauma victim, incapable of absorbing her parents' death and obliged to grieve for them at second hand. That's the easy, clinical rationale, and war's thunder does continue to echo distantly on the soundtrack, as if in corroboration. Still, it isn't sufficient to account for the element of precocious eroticism that tinges her relationship with Michel, insinuated by the faint double entendre of the movie's title.

Paulette is a diminutive version of the femme fatale in film noir, batting her huge, liquid eyes and spurring the mesmerized hero on to ever greater acts of bloodlust - with one crucial difference: Paulette is no bad seed out of a horror movie, but a completely ordinary toddler. Though Clement doesn't stipulate her motives, we may deduce that they involve plain childish calculations of self-interest. Having lost one source of security and well-being, she casts around her environment and pragmatically reattaches her desires elsewhere. The supreme tour de force of Fossey's naturalistic acting occurs in the aftermath of the bridge disaster. Touching her mother's cheek and then her own, Paulette puzzles over the rudimentary concepts of warm and cold, alive and dead. The impious rites with corpses, the whole film, might be explained by the necessity of returning, again and again, to this compelling riddle that reality has tossed up.

For kiddie necrophilia, Paulette has no rival - unless it be young Tootie Smith, who ascribes four fatal diseases to her rag doll and babbles endlessly about homicide in Vincente Minnelli's so-called family musical "Meet Me in St. Louis" (1944). Much later, another little girl would use scrambled Christian ritual to commune with her deceased mother, in Jacques Doillon's "Ponette" (1996). Yet "Forbidden Games" is perhaps the one movie wholly dedicated to the radical Freudian proposal that living matter seeks the comfort of oblivion. Seductive and troubling, it remains the chief embodiment of the death drive in cinema.

Peter Matthews (The Criterion Collection / Sight & Sound)

Za EX FILMOFILE Anamnesis

6/21/2012

Maršal Žukov

Dvodijelni dokumentarni film ruske proizvodnje (2010) otkriva zašto Staljin nije odlučio uništiti zapovjednika Žukova te zašto je Hruščov mrzio idola milijunima Sovjeta.

HTV 1 - 23.06. (Trijumf vojskovođe) i 30.06.2012. (Posljednja bitka) u 20:10 sati.

Za EX FILMOFILE Anamnesis

HTV 1 - 23.06. (Trijumf vojskovođe) i 30.06.2012. (Posljednja bitka) u 20:10 sati.

|

| Jurij Ozerov: Bitka za Moskvu - Tajfun |

Za EX FILMOFILE Anamnesis

Pretplati se na:

Postovi (Atom)